In a previous blog Archaeologist Bob Sheppard at Heritage Detection Australia discussed the problem of determining if a piece of iron is ‘wrought’ or not.

This discussion centered around a single piece of iron found by the Past Masters on the Wessel Islands in 2013. If the artefact is wrought iron it could be evidence of an early smelting process.

As the Past Masters only have access to one piece of the iron no intrusive methods could be used in determining if the iron is ‘wrought’.

The solution to the problem is quite simple; for wrought iron cannot be used to create a permanent magnet.

So how do we test this?

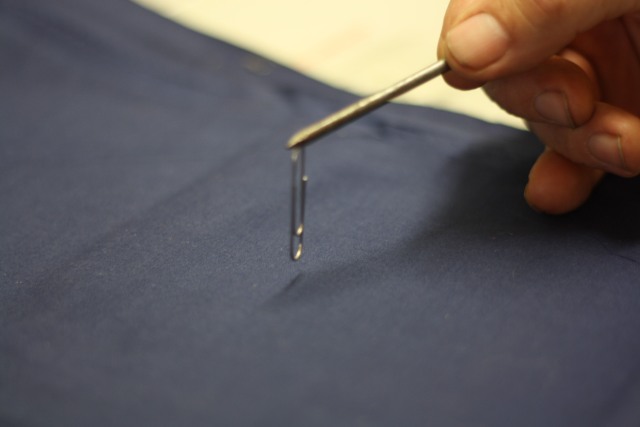

In this experiment HDA uses a small magnet, a nail, a paper clip and a possible piece of wrought iron (from the Wessel Islands).

Using the magnet the nail is stroked to induce magnetism. After the magnet is removed the nail retains its magnetism and will pick up a paper clip.

The wrought iron is stroked using the same process (the plastic bag is used to protect the artefact from scratching or contamination from metal in the magnet in case of later XRF analysis). After the magnet is removed the wrought iron will not pick up a paper clip.

Wrought iron is magnetic (attracted to a magnet) but it will not retain its magnetism. Carbon steel will.

While not completely definitive this field test for wrought iron is valuable. If you are an archaeologist locating ferrous material which is in the region of pre-1870 and you cannot magnetise an iron fastener there is a strong chance it is wrought. Steel, which can be magnetised, was mass produced from the 1870s thanks to the Bessemer process (Wells 1998:81)

HDA is not completely sure why wrought iron cannot be magnetised. Perhaps an electrical engineering specialist has an explanation which could be shared in the blog comments?

It may be related to the iron silicate slag. ‘Wrought iron is best described as a two-component metal consisting of high purity iron and iron silicate- a particular type of glass type slag. The iron and the slag are in physical association, as contrasted to the chemical or alloy relationship that generally exists between the constituents of other metals. Wrought iron is the only ferrous metal that contains siliceous slag (Aston and Story 1942:1)’.

Carbon steel, which became popular in the mid-19th Century, can be made into a permanent magnet.

It is important to note that some high quality carbon steel was created earlier than the 19th Century. This is especially true of tools, knives, surgical equipment and other specialised items. Therefore it is possible to find early steel which can be magnetised.

In 2013 Heritage Detection Australia carried out a archaeo metal detection survey of Long Island in the Abrolhos for the Western Australian Museum and numerous iron fastenings were located. If HDA had been aware of this simple field test an on site diagnosis as to whether or not the material was wrought, and possibly associated with the Batavia (1629) could have been carried out.

Likewise, this test could have been used by HDA in its field analysis of ferrous material found using archaeo metal detection and which possibly related to the wreck of the Vergulde Draeck (1656) such as the fastener below (which is now in the WA Museum collection).

Credits.

Thanks Hannah Sheppard for taking the photos.

References.

Aston, J and E B Story, 1942. Wrought Iron: Its Manufacture, Characteristics and Applications, A M Byers: Pennsylvania.

McAllister, M. and R. Sheppard 2012 Long Island Metal Detector Survey Report Prepared for Western Australian Museum Maritime. Fremantle: Western Australian Museum Maritime.

Wells, T 1998 Nail Chronology: The Use of Technologically Derived Features in Historical Archaeology, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 78-99.